Shortly before arriving to the Algonquin Park access point at Kawawaymog Lake while travelling from South River, you’ll leave the French River Watershed and enter the Ottawa River Watershed.

Watershed boundaries are defined by heights of land which direct the flow of water toward one common point.

Algonquin Park western boundary & The Algonquins of Ontario Land Claim area is formed by the Ottawa River Watershed boundary.

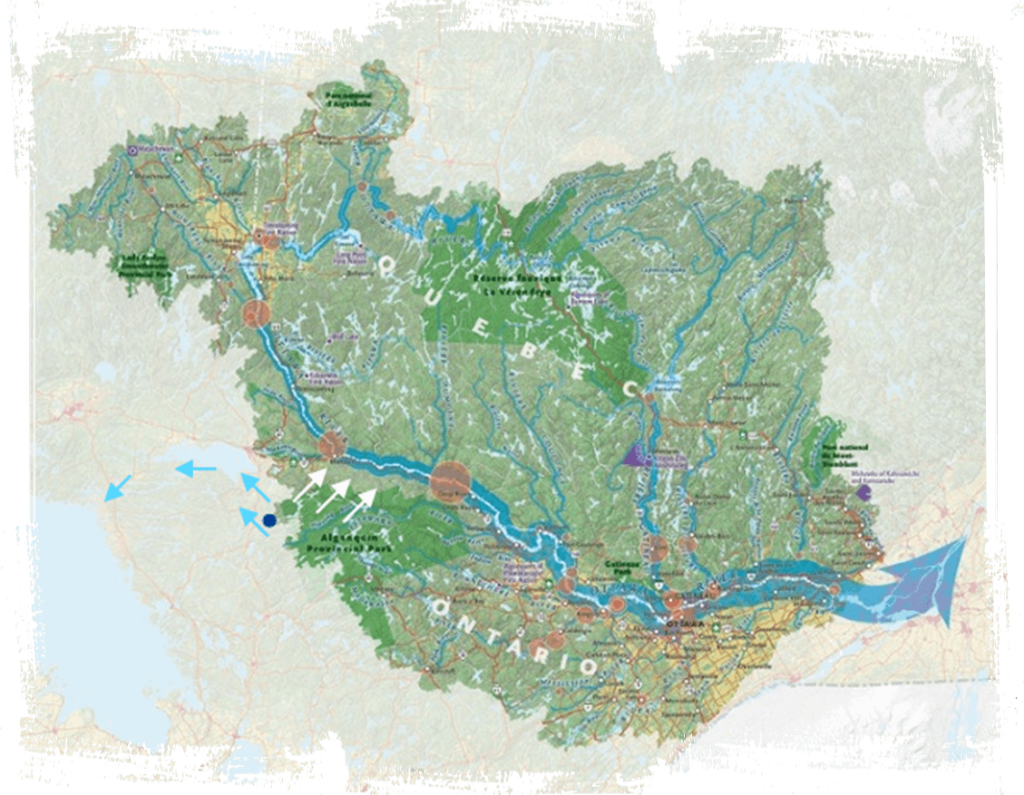

Blue arrows show the French River Watershed. White arrows and large green area show the Ottawa River Watershed.

All water that you see to the east of the watershed divide flows into Algonquin Park and to the Ottawa River before flowing past Ottawa and Montreal when it enters the St. Lawrence River and eventually makes its way to the Atlantic Ocean. But, all water to the west of this point flows west towards the South River flowing to Lake Nipissing and the French River into Georgian Bay.

Downstream Both Ways: From here visitors can paddle downstream east into Algonquin Park on the Amable Du Fond River from Kawawaymog Lake or downstream west to South River on the South River!

How long do you think it takes water traveling west to catch up to the water flowing into the Ottawa River? A drop of water taking the longer route has to go south from Lake Nipissing, all the way around the southern boundary of Ontario, through the Great Lakes Huron, Erie, and Ontario and over Niagara Falls before making it to the St. Lawrence River!

Algonquin territory

This highland point also marks the boundary of the traditional hunting and fishing territory of the Algonquins of Ontario. For thousands of years, First Nations people have gained sustenance from these lands. Archaeological information indicates that Algonquin people lived in the Ottawa Valley for at least 8,000 years before the Europeans arrived in North America, at which point their lives were forever changed.

The Algonquins of Ontario (AOO) and the Governments of Canada and Ontario are working together to resolve a land claim through a negotiated settlement. If successful, the agreement we reach will take the form of a modern-day treaty with aboriginal and treaty rights. Learn more about Algonquin treaty negotiations.

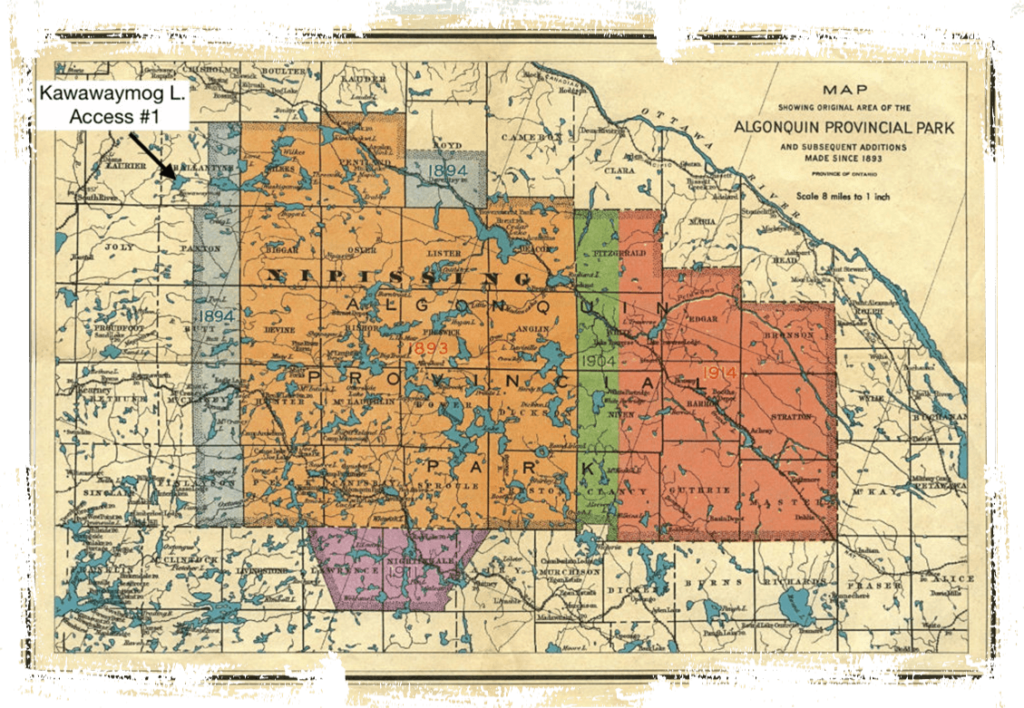

Establishment of Algonquin Provincial Park

The original Park area, consisting of 18 townships (approximately 3797 square kilometres), was designated in 1893 as Algonquin National Park of Ontario under the Algonquin National Park Act. The Park’s name was subsequently changed in 1913 to Algonquin Provincial Park, and since 1893 the Park has had its boundaries amended eight times to include 15 additional parcels of land.

This map was originally produced by the Chief Geographer’s Office, Surveys and Engineering Division 1946. Paper map acquired by Jeffrey McMurtrie. Scanning, stitching, and image processing by Mark Rubino.

Access #1 on Kawawaymog Lake is the starting point for some of Algonquin Park’s most beautiful and remote canoe routes.

Algonquin Park was established in 1893, not to stop logging but to establish a wildlife sanctuary, and by excluding agriculture, to protect the headwaters of the five major rivers which flow from the Park. Soon it was “discovered,” at first by adventurous fishermen, then by Tom Thomson and The Group of Seven, and a host of other visitors who came by train and stayed at one of Algonquin Park’s several hotels.

Over the years the Park has earned unconditional devotion and worldwide fame. More than 40 books have been inspired by the Park, and the list keeps growing. There is an Algonquin Symphony, paintings of Park landscapes hang in the National Gallery and hundreds of studies done on its protected flora and fauna have established Algonquin as the most important place in Canada for biological and environmental research.

Reconciliation

Algonquin petitions to the Crown seeking recognition and protection for Algonquin land and other rights date back to 1772. In 1983, the Algonquins of Pikwàkanagàn First Nation (known at the time as the Algonquins of Golden Lake) commenced the land claim by formally submitting the most recent petition, with supporting research, to the Government of Canada in 1983 and the Government of Ontario in 1985.

The Province of Ontario accepted the claim for negotiations in 1991 and the Government of Canada joined the negotiations in 1992.

On October 18, 2016, the Algonquins of Ontario and the Governments of Ontario and Canada reached a major milestone in their journey toward reconciliation and renewed relationships with the signing of the Agreement-in-Principle (AIP). The signing of the AIP is a key step toward a final agreement that will clarify the rights of all concerned and open up new economic development opportunities for the benefit of the Algonquins of Ontario and their neighbours in the Settlement Area in eastern Ontario.

A timeline – the arrival and subsequent impact of the Europeans

- 1603 – Samuel de Champlain makes contact with the Algonquins and was blown away by their furs

- 1608 – Leaving for France shortly after, Champlain returns and moves his fur trade upstream to a post to shorten the distance that the Algonquin were required to travel for trade

- 1614 – The French and Huron, who were Algonquin allies against the Iroquois, sign a formal treaty of trade and alliance

- 1615 – Champlain participates in a Huron-Algonquin attack on the Oneida and Onondaga villages (tribes who were part of the Iroquois Nation Confederacy)

- 1624 – The Dutch, who had been trading exclusively with the Iroquois, try to open trade with the Algonquin and Montagnais

- 1630-1700 – The Beaver Wars; The Iroquois, who had been displaced from the St. Lawrence Valley by the Algonquins, Montagnais and Hurons before the French came to North America first attempt diplomacy to push further north but when the Huron and Algonquin refuse, a war begins.

- The Iroquois Confederation led by the Mohawks mobilized against the largely Algonquian-speaking tribes and Iroquoian-speaking Huron and related tribes of the Great Lakes region. The Iroquois were armed by their Dutch and English trading partners; the Algonquians and Hurons were backed by the French, their chief trading partner.

- 1755-1763 – The Algonquin remained important French allies until the French and Indian War as the Seven Years War was known in North America

- 1760 – The British had captured Quebec and were close to taking the last French stronghold at Montreal. The war was over and the British had won the race for control of North America.

- 1760 – In mid-August, the Algonquin and eight other former French allies met with British representative, Sir William Johnson and signed a treaty in which they agreed to remain neutral in future wars between the British and the French.

- The Algonquin homeland was supposed to be protected from settlement by the proclamation of 1763, but after the revolution ended in a rebel victory, thousands of British Loyalists left the new United States and settled in Upper Canada

- 1783 – To provide land for these newcomers, the British government chose to ignore the Algonquin in the lower Ottawa Valley and purchased land from an Ojibwe Chief.

- 1812-1814 – Algonquins fought alongside the British during the war of 1812 and helped defeat the Americans at the Battle of Chateauguay.

- *Their reward for this service was continued loss of land to individual land sales and encroachment by American Loyalists and British immigrants moving into the valley.

- 1822 – The British were able to induce the Mississauga near Kingston on Lake Ontario to sell most of what remained of traditional Algonquin land in the Ottawa Valley. The Algonquins had never surrendered their claim but received nothing from its sale.

- 1840s – Further losses occur as lumber interests moved into the Upper Ottawa Valley.

- 1850s – Legislation and purchases by the Canadian government eventually established 10 reserves, one in Ontario and nine in Quebec for Algonquin use and occupation. These reserves only secured a tiny portion of what was once their original homeland.

On Tom Wattie

Trolley used on Standard Chemical railroad between South River and Round Lake – Tom Wattie and friends sitting in railway trolley pulling a cart with canoe and equipment to go into the Park. Standard Chemical Company had charcoal and wood alcohol plant at South River.

Tom Wattie, Park Ranger at Kawawaymog Lake (North Tea Lake), Algonquin Park from 1909-1929 was friend of Tom Thomson. Here he shows off his baking skills.

Tom Thomson had a close friendship with Tom Wattie, the Park Ranger stationed on North Tea Lake. They first met in 1913 when Thomson paddled north through the Algonquin lake chains. Wattie and his family lived in South River, but owned a small cabin (camp) on an island on Round (Kawawaymog) Lake, at the western edge of the park. Visitors to the area can stay in this updated cabin today. In the fall of 1915, Tom Thomson, Tom Wattie and local South River doctor, Dr. Robert McComb, spent several days at the camp. While Wattie and McComb went hunting, Thomson painted, and in a frenzy it would seem. Although several birch board paintings fueled the nighttime campfire, at least 5 remain from that time: Sand Hill, White Birches on Round Lake, The Tent, Dawn on Round Lake, and Chill November (which was also set on Kawawaymog Lake, but painted the following winter in his Toronto studio). Learn more at the story panel in Tom Thomson park.